Song Lyric Translations

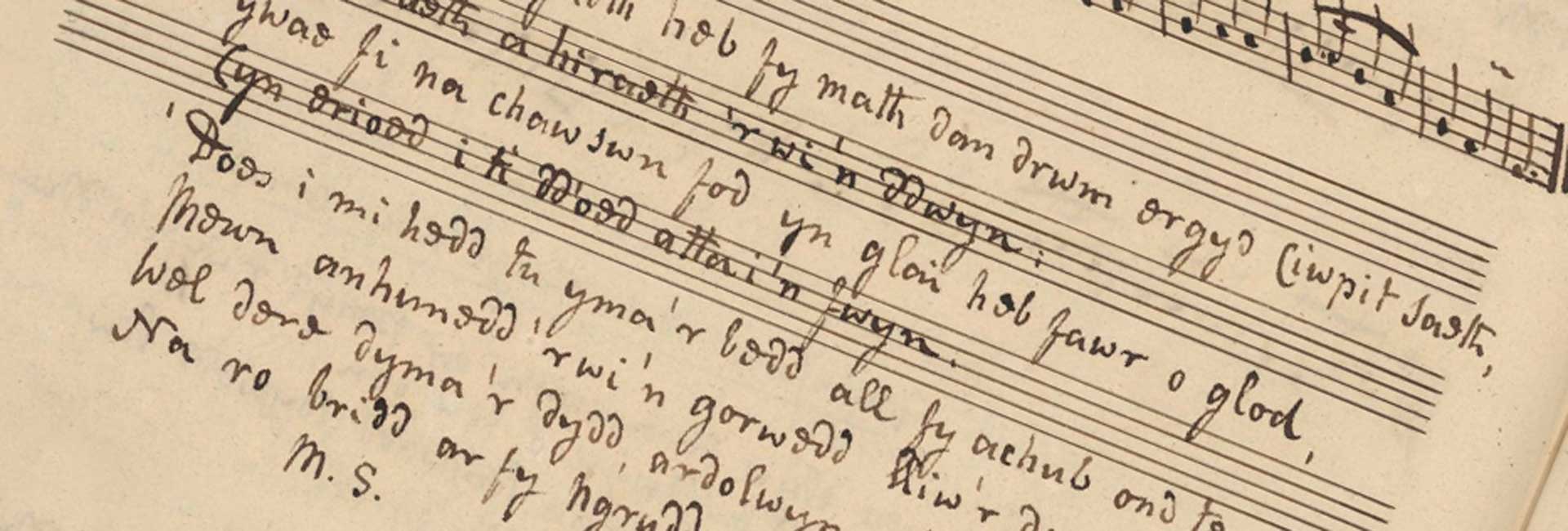

One aspect which sets Welsh folk music aside from other British indigenous music forms is that there is great emphasis on the written or spoken word. Melodies are often used as vehicle for supporting and heightening the literary prowess of the bard or author, rather than an end in themselves. Many songs also stem from, or follow very old poetic forms such as ‘tri thrawiad’ and contain complex internal rhyming and alliteration. As a result, melodies tend to be shorter and simpler when compared to their British and Irish cousins.

Whilst I would ideally like to print English translations of my song lyrics album booklets, there wouldn’t be much room for anything else and so I’ve therefore made this page of translations for this who wish to know more about the songs and the stories behind them. I’ve also included the relevant background information next to each song.

Please note: These translations are mostly literal, rather than poetic attempts at translation. Translating Welsh verse into English and doing it justice is very tricky (and something which I’ve yet to master!)

Click on a song title to be taken to the song.

Dilyn Afon

1. Cân O Glod I’r Clettwr

2. Dole Teifi / Lliw’r Heulwen

3. Y Ddau Farch / Y Bardd A’r Gwcw

4. Y Deryn Du

5. Taith Y Cardi

6. Y Fwyalchen Ddu Bigfelen

7. Lliw’r Ceiroes

8. Broga Bach

9. Cân Dyffryn Clettwr

10. Myn Mair

11. Ffarwel I Aberystwyth

Shimli

1. Helmi

2. Cornicyll

3. Mae’r Nen Yn Ei Glesni

4. Shili Ga Bwd

5. Y Medelwr

6. Cwm Alltcafan

7. Pryd Y Potsiwr

8. Cwrw Bach

9. Pont Llanio

10. Pysgota

11. Faerdre Fach

Dilyn Afon

Can O Glod I’r Clettwr (Song Of Praise To The Clettwr)

Were it not for T. Llew Jones’s original BBC Wales programme, this captivating song by Daff Jones would have disappeared forever – indeed it sat in the BBC archives for over 40 years before it saw the light of day again in 2016. It’s also peculiar also that it was not among the songs recorded by Roy Saer from Daff when he visited the old blacksmith in his home in Rhydowen in 1968. No record survives of the song’s origins or its title even, in oral or notated form, so we should therefore be grateful that it has survived at all.

The melody itself is fairly typical of many melancholic Welsh airs, but it also stands on its own as a succinct and unique composition. The words reveal perhaps slightly more about the songs origins, as the balladeer describes a life’s journey from birth to death along the banks of the Clettwr river which starts its journey on the marshland above Talgarreg village and flows into the Teifi near Dolbantau Mill on the border with Carmarthenshire. Though it’s evident in this case that the Clettwr river is the object of the author’s praise, the use of the word ‘hogyn’ (boy) is interesting. Since ‘hogyn’ is not a word generally in use in Southern Ceredigion, this suggests that the song originally travelled from somewhere more northerly (and from some other valley perhaps) and has been adapted for this river. I’ve therefore taken this a step further and ‘Ceredigionised’ the second verse in order to make it even more local.

Along the banks of the Clettwr, as a child I was raised,

And soothed to sleep by the sound of her waters

And there I played, a young sprightly child,

Trying to catch trout along the creeks of little Clettwr

The water turns mills as it goes on its way,

And the wheel of the factory too, like in the olden days

Among the thorns and the gorse, she emerges on the moor,

And the flow of wild flowers, around her precious banks

And when comes the day of my burial, break my grave,

Along the banks of the Clettwr, in the sounding of her waters

Dole Teifi / Lliw’r Heulwen (Teifi’s Meadows / The Colour of the Sunlight)

This track marries two songs along similar themes – love and deceit.

The first song, which forms the verses, has taken many lyrical and melodic forms in Ceredigion. It has also been noted down as Nos Galan and Y Bobl Dwyllodrus and appears in more than one manuscript and field recording. The melody in this version comes from the very north of the county and the words are an amalgamation of those sung by Thomas Rowlands, a farmer from Lledrod and Thomas Herbert, Cribyn (noted by J Ffos Davies around a century ago). Here an infatuated young man asks a friend for love advice and is told to play ‘hard to get’ – only to leave it too late and find out a year later that the object of his affection is engaged to another suitor (notably we never find out if it is his friend!)

The second part of the song which forms the chorus – Lliw’r Heulwen is from Mynydd Bach near Llanrhystud. It could easily be the same heartbroken young man as in the first song, as he pours out his affection, only to become exasperated by the apparent mercurial nature of a woman’s heart and resign himself to a life of singledom.

The green grass on the banks of the Teifi

Has tricked many a cow into drowning.

Many a girl has also tricked me

To leave the straight road for the desolate track.

One morning I was walking

Between the grass and the small trees.

There I met a neighbour,

One of the two-faced traitors.

The first thing I asked him —

How to love a girl and support her?

“Put aside her company for a year;

Little by little she will come to love you more.”

Colour of sunlight on the hills, colour of the lily upon the hill,

When you go from here, my dear remember this:

Your looks, your hand and your gracious manner, girl,

And your gentle, pretty nature has attracted my love.

I took that old fool’s advice;

For a year I gave her up.

After a year I went back

Thinking I would then have her company.

The girl gave an answer easy to understand —

“You have failed to get anyone else,

So, go far away, don’t come close,

I marry before the weekend.”

It’s very easy to recognise a hare, running in all haste;

It’s very easy to recognise partridges when they rise in a clamour;

The great oak amongst the little clover;

Woe is me that it’s not so easy to know a fair girl.

The mill must grind when it has water;

The smith must work while the iron remains hot;

The sheep must love the little lamb while it’s weak;

I must accept whoever is suitable for me.

Y Ddau Farch / Y Bardd A’r Gwcw (The Two Stallions / The Bard & The Cuckoo)

This is another track consisting of two songs which exhibit similar lyrical themes, this time anthropomorphism and animal communication.

The first, ‘Y Ddau Farch’ was collected from a native of Llangeitho in Ceredigion. The song is a conversation between two horses, with the older lamenting his lost youth and the redundancy of old age. It struck me that the merry nature of the original melody sat somewhat incongruously with the sad sentiment of the narrative and so this new version is intended to reflect this.

The second half of the track is an extract from the verses of ‘Y Bardd a’r Gwcw’ written by Daniel Jones or Daniel ‘Sgubor’ (1777-1859), a vagrant balladeer who sometimes took up residence in a barn in Castell Hywel. A conversation between a bard (possibly Dafydd himself) and the late returning cuckoo, this joyful exchange hailing the return of spring became very popular and travelled all around Wales, adopting a variety of melodies and words. Taken from the singing of Daff Jones, Rhydowen in 1968, recorded by Roy Saer.

When I was walking one morning,

Strolling from my little patch,

On the mountain I met

Two horses conversing.

The weakest horse

said to the stronger —

“Once, when I had respect,

I was as good a horse as you.”

“When I grew old and lame

I carried the corn to the mill,

And what I got

Were the poor leavings of husk.

“They took off my shoes

And sent me to the mountain,

And while I still breathe

I shall never go home.”

Oh Cuckoo, Oh Cuckoo, where have you been so long?

Before you came to the neighbourhood you quietened,

You missed your moment by two weeks almost,

You come at last with your merry song.

“I lifted my wing high up to the wind,

Thinking I would be here three weeks early.

Oh, don’t misunderstand, nor think so foolishly,

It was the cold north wind that held me back.”

Oh Cuckoo…(etc)

Y Deryn Du (The Blackbird)

This song of question and answer was once very popular across Wales. The form of conversing with birds has a literary tradition in Wales dating from the classical period of Dafydd ap Gwilym. Named canu llatai (llatai means love-messenger), such pieces usually involve a love-struck poet sending a bird with messages of love to a sweetheart. What sets this work apart from other llatai songs is that the author has not yet set his heart upon someone – instead the deryn du (a blackbird) acts as an avian dating service, listing all the apparently eligible local women!

Reviving this song required a little bit of detective work. The words were printed on a ballad sheet by Gomer Press, Llandysul, around the end of the 19th century but without a melody. I somehow managed to locate it in an obscure field recording of Tom Edwards, Flintshire in the British Library in London (recorded 1953). The accompanying notes said that it had been written around the middle of the 18th century by a mole catcher called David Jones from Llandysul and has also been noted as being sung by the famous balladeer ‘Dic Dywyll’ (Blind Dick) in Caernarfon in the 1830’s, so clearly this is a song which has travelled far and wide.

Blackbird, you who travels my lands,

Oh, you who know the old and new,

Will you give counsel to a young lad

Who has been pining for more than a year?

“Oh, come closer, lad, and listen,

To find out what ails you,

When either the world turns against you

Or you pine for someone’s love.”

Oh, it’s not the world that turns against me,

Nor do I pine for someone’s love,

But I see the fair girls becoming scarce

I don’t know where to turn for love.

“Do you like the old widow,

Her coat full and close to death,

Her black cows in her herd?

She will be of great benefit to you.”

I don’t like the old widow,

Her coat full and close to death,

Nor her black cows in her herd.

For a poor lad she isn’t suitable.

I don’t want her, Blackbird.

“Do you like the farmer’s daughter

who is a compassionate and merry flower,

who puts her money away in corners

And can leap a leap for every one of yours?”

Well, a hundred farewells to you, bird,

Well, this is the girl that I will go and ask.

While ship on sea and shingle in river

I will never want but for the farmer’s daughter.

Farewell to you, farwell to you, Blackbird.

Taith Y Cardi (The Cardi’s Trip)

Prior to Dr. Beeching’s infamous axing of local railway services in the 1960’s, Llandysul was one of many bustling regional stations on the West Wales line, transporting people, stock and goods across the country. A semi-Welsh version of the English ballad ‘The Charming Young Widow’, this tale of infatuation and deceit takes place on an ill-fated train journey from Llandysul to London.

Printed by Gomer Press around the turn of the last century, this is an adaptation of a macaronic song (a piece containing a mixture of two languages). It is unusual in the sense that it not only contains a lot of English, but that it does so in such a humorous manner. Llatai folk songs are known for often containing call and response in English and Welsh – indeed many Welsh ballads started life as English works – however the author of this ballad decided to use what could only be described as ‘Wenglish’ to tell his tale. It is unknown whether this was intended to be ironic, or is simply due to a poor grasp of the English language (the majority of Welsh speakers were monoglots at the turn of the 20th Century)

I live in Llandysul in Cardiganshire,

A letter informed me my uncle was dead.

And to go with great haste by train up to London

As hundreds of pounds was left me,’twas said.

So I was determined to go on my journey,

Book my ticket, first class, I was fine!

A widow and I side by side sat together

In the carriage was no one but us and no more.

Silence was broken by my purty companion

And then conversation, indeed ’til my brain

Was going on the dizzy—I almost went crazy

For the little fair widow that I seen in the train,

The little fair widow I seen in the train.

By this time the train it was come to the station,

A couple of miles from big big one in town.

The widow she say as she look thro’ the windows

Good goodness alive why there goes Mr. Brown.

Now she was disappeared, the guard whistle blowin’,

The train was a-moving but no widow appear.

With a puff and a puff it was off, I was afraid,

My watch! Oh! Where was it, and where was my train?

My purse and my ticket, loose tickets were gone,

When I found out my loss, indeed I was cryin’ —

“O dear, o dear, dear Mam what shall I do?”

The little fair widow, well she steals on the train.

The little fair widow, she steals on the train.

Y Fwyalchen Ddu Bigfelen (The Yellow Beaked Blackbird)

Copied from the singing of Mrs. J Emlyn Jones in Ceredigion and noted in the Welsh Folk Society journals, this melody is a variant of Cân y Lleisoniaid, which was at one point popular throughout South Wales. The manuscript notes that the compiler had replaced half of the words (which are incomplete) with those of his own, interlacing them with English (this stems from a practice in Glamorgan where Welsh colliers met English workmen for the first time). I have therefore used the Welsh words written by Llew Tegid.

This is another song which features a conversation with a blackbird – however it could be debated whether this song could be included in the llatai category at all since the ‘beloved’ in question is not a woman, but Wales itself. It is in essence a song of hiraeth by a boy who has crossed the border into England and is longing for his homeland, embodied in song by the mellifluous calls of the blackbird.

Oh, yellow beaked black bird,

Enchant the heart with your early song.

Sweet notes of a merry heart

Wakes the choir of little birds.

Come and listen to the complaint of a boy

Who is in heartache night and day:

A cruel longing pursues him,

Longing breaks his sad heart.

Leaving the elegant vales of Wales,

Leaving the enchantment of the land of song,

O so difficult is separating

A pure Welshman from fair Wales.

Your notes evoke the hearts longing

As you tarry in the Englishman’s land,

In memories of Coed-fron

Where once your voice was so dear.

Lliw’r Ceiroes (Colour Of Cherries)

I came across this unusual melody in a large collection of manuscripts called ‘Melus Seiniau’ by the renowned song collector Ifor Ceri (also known as John Jenkins). Jenkins collected tunes and melodies from across Wales during the first half of the 19th century, including many from Ceredigion. Lliw’r Ceiroes (Colour of Cherries) is noted as originally being sung by Evan Thomas from Llanarth and it is recorded here for the first time.

The song follows the heartache of a young man who’s likely put his foot in it with his sweetheart and is now asking for penance. Lliw in Welsh can mean both ‘colour’ and ‘appearance’ and so Lliw’r Ceiroes or ‘Colour of Cherries’ in this case, is a nickname or term of endearment for his beloved who he is so desperately trying to win back. This song is a good example of Welsh verbal ingenuity; although not in strict cynghanedd (a metre unique to Welsh), it does contain a great deal of free alliteration.

Colour of cherries hear my complaint

And the penance that I bear.

Dear, beautiful woman, clear like the wave’s complexion,

For liking the good girl, the fair one, shining complexion,

Was to live, despite the wound beneath my breast.

I’m enslaved without my peer, below the blow of Cupid,

Doubt and longing I bear,

Woe is me that I could not be hidden away without much praise

Before you come dearly to me.

Give me peace, and save me from my state

I’m tired and sleepless complexion,

Come the day, please set me free,

Do not put earth on my cheeks, perfect woman.

Broga Bach (Little Frog)

Collected from the Llandysul area at the turn of the last century by a member of the Welsh Folk Song Society, this uniquely Welsh version of the Anglo-American tune ‘Frog Went a Courtin’ is almost unrecognisable from the popular tune which inspired it. This song was noted down in the mixolydian mode, a musical scale highly uncommon in Welsh folk music and therefore exudes a slightly eerie quality which is very different to the frivolous and merry nature of the English original.

There are lyrical similarities between the two versions, which could be said to be akin to a nursery rhyme – however the uncanny nature of this melody takes it in a different direction altogether. Only two verses were noted down in the Welsh manuscript and so the rest of the song has been translated from the original to complete the story.

Froggy went a-wooing ride, twy wy ei di o

Am i dym da e dym to,

When upon his high horse set

Am i dym da e dym to.

Little mouse did little froggy spie, twy wy ei di o

Am i dym da e dym to,

To make a wife and be his bride

Am i dym da e dym to,

Dearest love, do you see

I am very fond of thee,

And the kindly mouse to him

Answered with a beaming smile.

Take me to the gleaming church

We’ll be married in due course,

Mole he can officiate

Then lots of food to fill our plates.

Little frog, dear little frog etc

Cat came to the neighbourhood

Trapped the mouse near where she stood,

Little frog ran off for his life

Leaving there his dearest wife.

One duck on the millside pond

Swallowed little froggy – gone!

That was the ending of the two

And a romance which went askew.

Little frog, dear little frog etc

Cân Dyffryn Clettwr (Song of the Clettwr Valley)

This song, which is unique to the Clettwr valley, is noted in tonic sol-fa notation at the back of Hanes Llandysul (A History of Llandysul, 1896) by Gomer Press. I also uncovered a recording of Kate Davies, Prengwyn, singing it for Roy Saer during the sixties. Kate, a keen historian, author and singer, was likely the last person to have learned this song orally.

Originally composed by Edward Rees of Talgarreg, this song captures that most universal human desire for adventure and notes the sometimes capricious nature of the open road – or in this case, the sea. A tale of a mab afradlon (a prodigal son), the song’s protagonist leaves his cynefin alongside the banks of the Clettwr and goes to sea as a sailor, only to find that life is tough and that he soon has hiraeth (longing) for the comforts of home.

Yes, I spent a merry time

In the school in Llwynrhydowen,

And by following the fishermen

Along the banks of the Clettwr.

After finishing with the schools

I turned out to be a prodigal son,

And I went as a sailor boy

Beyond the sight of Clettwr Valley.

After the winds became silent

And the harsh waves became still,

The seaman felt disgraced —

He should return to Clettwr Valley.

I’ve walked the meadows of Aeron,

And embraced the blessed girls,

But the seaman much prefers

A fair girl from Clettwr Valley.

Myn Mair (By Mary)

This galargân (lament) was noted down from an elderly woman named Myra Evans in New Quay in 1963 by Robin Gwyndaf, who had been tasked by the Welsh Museum of Folk Life with recording as many old folk songs as possible before they passed from living memory. Along with his colleague Roy Saer, they amassed quite a remarkable collection of recordings. Myra was the last known bearer of this song.

This is the only surviving gwylnos song in Wales and was sung as part of a wake the night before a funeral by friends and relatives of the deceased. There is to this day a tradition in Wales of keeping bodies in the house and receiving visitors until the funeral and so this song would have formed part of a communal grieving process. The song is in essence a petition to Mother Mary that she (or anyone else with a VIP pass at the pearly gates) might watch over the soul of the recently deceased, which in the case of this song is likely to be a child.

The Catholic nature of the words indicate that this song is very old indeed. It seems it was sung and kept alive in secret for many hundreds of years following the reformation, with banishment from the chapel and public disgrace the likely outcome for anyone caught singing it.

My pennies I’ll give for the soul locked up,

My candle I’ll give in the parish church,

I’ll say mass fervently seven times seven times

To keep safe his eternal soul. Mary wills it,

Mary wills it, Mary wills it, Mary wills it.

Saint Paul and Saint Peter, all saints of heaven,

And Mary, Mother of God, entreat with all seriousness

That he may have peace, and rich relief,

Open paradise, and the arms of his Father.

Mary wills it, Mary wills it, Mary wills it.

Jesus’ Mother, most beautiful woman in the world,

Virgin Queen of all the heavens,

Pretty lily of the valley, fair rose of heaven,

Entreat with all seriousness on behalf of my friend’s soul.

Mary wills it, Mary wills it, Mary wills it.

Ffarwel I Aberystwyth (Farewell To Aberystwyth)

Ceredigion has a rich history of coastal trade and seafaring. This track conveys the hiraeth (longing) of the sailors as they left Cardigan Bay, naming the places and people they had left behind. The bulk of the track consists of a tune collected by Jennie Williams for the 1911 Eisteddfod folk song collecting competition. This melancholic air was sung to her by Dan Evans of Aberystwyth. Williams also collected songs from Evan Rowlands (a butcher on Pier St, famed both for his singing and the giant stuffed bear outside his shop) who had also heard the song being sung by local sailors.

The end section of the track is a fragment from a song Hwylio Adre (Sailing Home) in J. Glyn Davies’s book of Welsh sea songs and shanties. With the addition of this tune, the track forms a continual circle of departure and return, reflecting a common element of Ceredigion’s bygone coastal life. Many songs such as these would have travelled up and down the Welsh coast and across the sea, adding to the rich exchange in cultural, as well as material goods.

Farewell to Aberystwyth,

Farewell to the top of Maes Glas,

Farewell to the Castle tower,

And also Morfa Glas.

Farewell to Pen y Parce,

Farewell to Figure Four,

Farewell to the fairest girl

That ever opened a door.

Farewell to Llanrhystud

Where I’ve been many times

Loving according to my fancy,

But the work was in vain.

I did love her

For four and ten months,

We sometimes had bad weather,

Other times fair weather.

And sometimes I’d find her content

To listen to my complaint and cry,

But she gave her hand to another

And broke my heart.

To Calio I bid farewell,

To Calio I bid farewell,

Sailing home, sailing home . . .

Shimli

Helmi (Corn Ricks)

Words: Ifan Jones, except verse 4 by Owen Shiers

Before sileage took over as the dominant means of feeding winter livestock, and big bales came to pepper the fields like giant black spores, the rural Welsh landscape featured a diverse patchwork of various crops, including some which were used for human consumption. These would have been uniquely suited to the soil and topography of each region, and due to their diversity, offered resilience in the face of disease and unpredictable weather. Harvesting was a large communal affair, with parties of workers building corn ricks or ‘helmi’ as a means of storing the grain outside over the lean months.

This now redundant practice was immortalised by Prengwyn farmer Ifan Jones in his poem ‘Helmi’. In it he speaks of autumn advancing over the bare hills, ripping the leaves from trees as it sweeps through the landscape. In its face stands a silent army of ‘helmi’ in their golden liveries protecting the farmhouse from the onset of winter. Today, farmers pay thousands of pounds to dispose of the miles of black plastic they use to wrap their monocrop rye grass. One does wonder whether Ifan Jones would have thought it much of an improvement…

He comes cleaving the (wooded) slopes,

And bruising as he pleases,

And leaves scars in his wake

On the bare side of the hill.

Although his flash is bright

As far as the furthest boundary

The wake of the storm and the chill of the grave

Is on the face of withered creation.

They are this year again

Protecting my father’s house;

I know watching the strong army,

That autumn’s to come to the land.

If the old hood is a bonfire,

I do not fear the betrayal –

There is a strong retinue in golden liveries

Guarding my father’s house.

If they were scattered,

Without our esteemed ancient grain

How we retreat from the cold winter,

And its intrepid old claws?

Cornicyll (Lapwings)

Words: Owen Shiers

Since 1930, lapwing numbers in Britain have plummeted by 90%. Changes in agricultural practices have without doubt been a major factor in this decline as mechanisation, intensification and changes to arable farming practices have all deprived this spectacular bird of its natural habitat. Their incredible aerial acrobatics and spring mating rituals were once a common phenomenon in the skies of rural Wales, but they are now mostly confined to a small number of protected areas.

The poet and farmer Dic Jones, who was raised next to the RSPB reserve at Ynys Hir, commented on the disappearance of the lapwings in his poem ‘Cornicyll’ (meaning ‘lapwing’ — however they are also known as ‘Hen Het’ in Ceredigion, as the name bears a similarity to their calls). This song is inspired by Dic’s poem and my own visits to the lapwing reserve at Ynys Hir and is a commentary on the bird’s disappearance from both the landscape and from cultural memory. Nowhere is this more poignant than the recent of example of the couple who bought ‘Banc Cornicyll’ farm in Carmarthenshire and then changed its name to ‘Hakuna matata’ — it means ‘no worries’, but try telling that to the lapwings who have been wiped from the landscape there, in this case both in a physical and linguistic sense.

On the edges of Ynys Hir, in the whispering sound of the wind

I heard the voice of the lapwing going on its way

A song from the sky, true and clear, now and then

Like that simple enough it came, to charm me near the shore

And then a flock came from the sky, flying towards the waves

And somehow a wave of peace came, quietly over me

Sprightly birds, fair birds they are every one,

Wheeling above the bare strand, like a divine air force

There they go with their swift wings, landing with a crash

Like a bunch of witty old pensioners, chattering by the water

And yet daring, yet hunting, the long enduring waters

Despite the harsh cold winter, for abundance on their journey

Here they are, a remarkable old force, without one showing disappointment

Do they see the shadow of progress now, across the barren landscape?

Oh how long, shall we see, their lively flight?

To see us through the long cold winter, messengers fair their world

There is talk that short will be the time of their greatness among us

but is the lapwing wiser than the noise of our sad anguish?

Mae’r Nen Yn Ei Glesni (The Heavens Are Greening)

Words: D. Jacob Davies

Like other parts of Britain, Wales has a tradition of singing May carols as part of its folk tradition. In addition to dancing the maypole, groups of singers would rise early and go from door to door singing carols to welcome in the spring (as well as wake up the neighbours!). In addition to heralding the arrival of the new season, the singing of such songs was intended to rouse the earth’s energies to help grow strong crops and ensure a fruitful growing season.

In Wales, such carols were traditionally composed to light poetic metres which often had a strong discernible rhythm. This carol ( ‘The Heavens are Greening’) by D. Jacob Davies, is composed in a metre called ‘tri thrawiad’ and is a vivid and vibrant description of the greening landscape, with us being aroused from our winter slumber by the fair spring breeze. The processional feel of the metre is fairly obvious; however it’s always struck me that the slow, plodding nature of this rhythm sits in contrast to the joy and liveliness of the season and so I decided to give it its own rejuvenation and speed it up a little…

The heavens are blueing and the flowers are fresh,

And the sun rises nimbly on a summer day;

My heart expresses its gratitude constantly,

In charming cheer I carol.

The birds sing and the morning is leaping,

And the breeze demands to take us from the house;

The cock comes with its crowing, the dawn comes with its invitation,

From her rising comes a call from bed.

Chorus

Heat comes to the valleys, the fields and the lakes,

And sun on mountains and rivers in haste;

Every place will be light, healthy, and me

Without pains or notes of cold

In afternoon there is sunbathing, laying and singing,

And the seagull cries while sailing in the sun;

And enjoyment for me is waiting for hours

On the shores of such pleasant acreage

May your days be easy and your fruits abundant,

We get wonderful smells on dunes and meadow;

On a bed of buds I rest from my labor

Heal the soreness of a sheltered sleeper!

Shili Ga Bwd (Wormwood)

Words: Dafydd Isfoel

Before the arrival of the NHS, hedgerow plants and home-grown herbs held a significant place in the medicinal toolkit of people in rural Wales. I was fascinated to learn about the properties and uses of a handful of herbs from two elderly brothers, Cerdin and Elwyn of Rhiwlig farm in Tregroes whilst visiting them in spring 2022 . The brothers hail from a family of herbalists including their sister Marged, who was renowned locally for her knowledge.

One plant which cropped up in conversation — and of which I have heard a few tales — is that of wormwood, known locally as ‘Shili Ga Bwd’. Until relatively recently it seems it was grown and used widely to treat a variety of ailments but has since pretty much disappeared from folk memory. In his poem bearing the same name, the poet Isfoel affectionately describes how his ailing mother, who tended the plant with great care, slowly succumbs to the frailties of old age and the plant withering and passing with her. It is a poignant piece of writing which captures both the care and nurturing aspects of both his mother and the plant.

Mum had a small bush until the end,

On it not a flower or a crop,

One humble and completely common,

Which she called shili-ga-bwd

She looked after it like a child

In every weather, be it cold or hot,

Bringing her decanter of the drug

To the thirst of the shili-ga-bed.

When a friend called on their journey

She was unchanging in her mood,

She presented each one before leaving

With a sprig of the shili-ga-bwd

Mother became infirm from old age,

And the bush clung to its bag,

And soured did the smell and cheerfulness

That was carried by the shili-ga-bwd.

The root withered from heartache

And the leaves withered in their sulking,

And when their keeper went into the earth

So too went the shili-ga-bwd

Y Medelwr (The Reaperman)

Words: Richard Davies (Isgarn) except verse 4 by Owen Shiers

Of all the Ceredigion’s folk poets, the poet Isgarn more than any perhaps encapsulates the essence of what it is to have one hand on the handle of the plough and another gripping a pencil. Born in 1897, Richard Davies (bardic name Isgarn) spent a life married to the rough pasture of his isolated farm at Iscaron near Tregaron. A hill shepherd by trade, he would walk the four miles and back to Tregaron each week to attend poetry night class where he learned the craft of cynghanedd. Only following his death was a body of his work published and did Wales realise what a gifted poet it had lost.

Isgarn’s poem ‘Y Medelwr’ is a direct response to the rapid shifting agricultural practices he witnessed in his lifetime. One common sight which he witnessed disappear entirely from the rural landscape was that of the ‘parti fedel’ or reaping party, that would go from farm to farm harvesting corn. The poem lovingly describes the relationship between the land and the corn reaper, with the fields, wincing under the weight of modern machinery, yearning for their slow methodical footsteps. Back in the ‘hendre’ (the winter dwelling place) a sickle hangs rusting and forgotten on the wall, a reminder of the reaping party scattered like seeds to the four winds.

The long acres under the cliffs

Where he once followed with his plough and harrow

Are uneasy, calling for him

Under a yellow ocean of pure grain

The summer matured his crop fields

His sheaf grew likewise at the same time

And he was seen carrying the crop at dawn

To the unceasing grain store of the great harvest

Chorus

But in the old town hanging on the wall

There sits an idle sickle like a steel rainbow

With rust eating it, piece by piece

And lost is the zeal that was once in its shaft

He was seen returning every time from his way

From the golden fields of old Hereford

But now his stay is hopeless

The homeless are walled off from God’s acres

Equipment comes to reap from hedge to hedge

A alluring promise of an easier task

But under the interference of heavy wheels

The land is writhing along the valley

Cwm Alltcafan (Alltcafan Valley)

Words: T. Llew Jones

We were fortunate as children in our tiny primary school in Capel Dewi to have the renowned author and poet T. Llew Jones come read to us from time to time. He had a certain way with children, a twinkle in his eye which spoke of mischief, wonder and of delight. As a child I devoured his children’s books, but it wasn’t until later in life that I came to appreciate his skill as a poet.

T. Llew had a way of communicating the profound in simple terms. He was also a ‘dyn ei fro’, a man very much of, and from, his ‘cynefin’. He found endless fascination in the people and places of his locality — and none more so than a place called Cwm Alltcafan. A deep wooded gorge near Pontyweli, Cwm Alltcafan is where the poet would spend countless hazy summer afternoons angling for a bite in the slow, swirling waters of the Teifi. His poem of the same name probes us with a series of questions. It wonders if we have been to such a place, then asks us if we find other places more exotic — daring us almost to declare them more heavenly. As tongue in cheek as his questions are, to me they challenge the modern malaise of escapism and displacement, reminding us of the beauty and simplicity that can sometimes lie right at our doorstep.

Have you been to Cwm Alltcafan

Where the summer lingers long?

Where there are the bluest bluebells

No really? No really?

Have you seen the river Teifi

Flowing slowly through the valley?

Did you see the gorse flowers?

On the slopes a heavy carpet?

Have I been to Switzerland? No,

Not in Italy Italy,

But I have been in Cwm Alltcafan

In June many times.

Go to Switzerland and Italy,

Or Ireland in your turn,

Go to Scotland, where there are

Magnificent views, I suppose

But to me give me Cwm Alltcafan

When summer is greening the world,

There is the best view,

And you can keep all the others.

Did you see the Alltcafan Valley,

Where are the trees and the deep river?

Go to Cwm Alltcafan,

But don’t tarry late… just in case!

Pryd Y Potsiwr (The Poacher’s Meal)

Words: Owen Shiers

During lockdown I was invited to compose a piece of music based on an interview with a man called Caradog Jones, who for over 40 years worked as bailiff of the river Teifi. The tape itself was nearly 50 years old, and so I assumed that Caradog was long since passed — however a chance meeting with his neighbour revealed to me that at 95, he was very much still alive and kicking! I was delighted soon after to meet him in person and be regaled with his tales of a life lived along the banks of the river.

As one of Britain’s finest fishing rivers, Caradog told me of the Teifi’s renowned bounty (it was said that in places you could walk from one bank to the other on the backs of the fish). As a plentiful source of food, he had his work cut out catching the many poachers who would venture under cover of night to her banks to snatch a salmon or two from a pool. Many ended up in court, but such was the plight of the rural population at the time, that this was often seen as a source of pride. Today, the river stands in a precarious state with the numbers of salmon a fraction of what they once were — some are even warning that this silvery nomad could disappear completely from the river in the next few decades.

The giant on the riverbank. his face hidden

A torch in one hand and a clutch in the flow

Barefoot creeping silently through the gravel

To catch a fish under the cover of night

Following autumn since time immemorial

Salmon ran up from the sea

And the boys followed, working as a team

To escape from the bailiffs on the banks of Teifi

When the moon is down and black, while it is the colour of night

Landing until the dawn, ends the poacher’s meal

Life was hard, and money was tight

And the occasional salmon was a rare treat

Standing in a court was not a subject of shame

For catching a fish by the water’s edge

There was enough to feed the residents of each neighbourhood

And feed all of London, so everyone said

But the landlords insisted on persecuting

The needy people on the banks of Teifi

Trouble is at hand while we pollute our land

Will the fright be enough to save the poacher’s meal?

Save the poacher’s meal

If you happen to be seen in a river or stream

The salmon leaping, by god don’t you

Take without need, so fragile now are

The fish that run the Teifi river

Cwrw Bach (Small Beer)

Words: Rees Jones (Amnon)

It was the custom in rural areas of West Wales in times gone by to keep an eye out for one’s neighbours. Many lived a hand to mouth existence and a bad accident or illness — or worse — could easily leave a family with no food on the table. ‘Cwrw Bach’, or ‘Small Beer’ was one such way of helping those in need. The practice involved a neighbour making a batch of home brew, inviting the neighbours round for knees up and selling the resulting beer to raise some much-needed cash. This song is an invitation to such a gathering.

Composed by the poet ‘Amnon’ or Rees Jones, Pwllfein (1845) from Talgarreg and set to a melody adapted from the singing of Kate Davies, Prengwyn, the song imaginatively speaks of the eternal tension between the various aspects of the human psyche. Mr. Need and Sir Selfish, Sir Shameless, and Master Generous all battle it out for dominance as the poet pleads with us to give credence to the better aspect of our nature and err on the side of generosity and benevolence.

I’m encouraging each one lovingly

It will be unwise for me to say, I’m quite unskilled

Mr. Needy will shoot some words

And maybe Sir Selfish will close my jaw

Needy and Selfish were in a spiritual battle

And their sharp arrows were quite adverserial

Sir Selfish was wounded by Sir Shameless

And then Sir Needy was appointed chief

Refrain

To the generous, to the generous and the charitable

Now there is Needy and Worry to tire me

I don’t get much peace of mind when I’m asleep or awake

The back is bare and the feet through the shoes

Oh it’s quite troublesome I answer the bills

To add to this council in worry and need

Came Shameless to bear in his forehead

And the advice I got from Needy and Worry

Was going around to inviting diligently

Every grade and every age of those who can

Giving respect and obedience to Mr. Generous

And remember to say ‘give a warrant to call’

The use of rib, cakes, napkin and beer

Pont Llanio (Llanio Bridge)

Words: Phil Rowlands

At the end of 2022 I was asked to compose some music for a short film being made by a community group about an old milk processing plant near Tregaron. From its origins as a humble 19th century dairy, Pont Llanio (which was run by the state-run Milk Marketing Board) grew to employ over 120 people in its 1960’s heyday. Workers would collect and process milk from all over West Wales and distribute it nationwide via the train station which sat next to the factory. The company became a real community hub and would often host events and concerts as well as entertainment for local children. It also sported its own cafe, football team and even had its own in house-bard: Phil Rowlands, who documented many of the key events at the factory through verse.

Today the place stands in ruins, abandoned and choked by weeds. The trainline closed with the Beeching cuts in 1967 and privatisation and followed not long after, with the factory closing in the early seventies. During my research for the film, I was fortunate to meet a few former employees who were generous with both their time and memories, including Lloyd Jones who gave me this poem by Phil Jones. Written on the eve of the closure, it reflects both the fondness of the employees towards their fellow workers but also the potential devastation they were faced with at that time. It’s fair to say the area has never recovered.

Farewell to all my friends, the big dispersal is near

Some stay here, and the rest moving away

Happy has been the co-working, throughout the long years

All tasks just like singing, and no one with their cheeks moist

Refrain

Who remembers, the Pont Llanio company now?

On the banks of the still Teifi, near Jac JP’s station

Memories will linger for the exploits of the happy many

For many a long yellow summer, with the sun and its heat so hot

The red labels and the churns, and the refined women

Or old icy winters, and everyone like ‘on his guard’

To prevent a sudden skid or slide and falling on the yard

For lightning and rain and tumult over hill and marsh and moor

Or the big snow one year that made some stay the night

Farewell Rhys John and Morgan, Wil Rees fine old boys

Who carried according to the counting, thousands of woodbine

Farewell to the amusing company on the entertaining rounds of the night

Everyone with their wit or a story, and no one pushing back

I don’t know what the history of Pontio Llanio will be soon

There are great stories about walking, but are they true?

Someone told to me but I can’t really believe it

That the creamery soon became a woolen factory, soon a woolen factory

Pysgota (Fishing)

Words: Isaac Davies

When the Benedictine monks arrived in St. Dogmaels from France in 1118, they carried with them an age-old fishing technique developed on the Seine River in Paris. This effective method, which utilises weighted nets, was quickly adopted by the locals and became the principle means by which people on the Teifi estuary sustained themselves for centuries after. Fast forward 800 years and dwindling numbers of migratory salmon and sea trout have led to strict restrictions on the numbers being caught, rendering the practice untenable.

Just before the pandemic I was invited to perform at a concert for the fishermen and their families in St. Dogmaels. There I learned first hand the devastation the abrupt demise of this tradition has caused — not only financially, but in the ending of an identity that this way of life engendered in these people over countless generations. For the concert I managed to uncover a mid-19th century ballad which speaks of the Teifi’s reputation for fishing and the sheer numbers of fish and eels in her waters. It is a song which stands in stark contrast to today’s precarious situation, with the salmon’s survival in the river anything but certain.

I’m going fishing, in the summer, in the summer

Where shall I go first in the summer?

Maybe the Honddu River?

The green banks of the Tywi?

The hard rocks of the Cothi?

And also the Teifi Tiver in the summer

To Llandysul I’ll go first in the summer

To catch a fish in the summer

Some are encouraging me in Newcastle Emlyn

To have oat cakes and butter

And a pint of butter-milk in the summer

Aberteifi is remarkable in the summer, in the summer

For catching eels in the summer

But what is remarkable

I can’t find knowledge

Despite searching for many days

Of feathers for eels in the summer

If I can’t catch, in the summer, in the sumer

After fishing in the summer

I’ll go to the Black Lion in Llambed

And there I will seee

A crew of women

Flowers of the summer, flowers of the summer

If I get a comfortable place in the summer

I’ll spend two months there in the summer

I’ll insist on liveried servant, four horses

To drag me night and day

Through all the places in the summer

Through all the best places in summer

I’m going to go fishing

Faerdre Fach

Words: Owen Shiers

Whilst researching material for the first Cynefin album I met a cheery elderly chap called Edgar Thomas who had at one time been a keen musician. Edgar was very helpful and generous with his time, and I would go round to his house in Llandysul from time to time for a paned (a cuppa), where he would reminisce about the good old days as a plucky youth growing up on the busy Faerdre Fach farm just over the valley beneath Pencoed Foel Hillfort.

The fort itself dates to the Bronze Age and there are rumours in the locality that Owain Glyndwr himself may have been born there. Faerdre Fach dates to at least the medieval period and is clearly of historic significance… but all this passed the new owners by when they decided to start a petting zoo and renamed it, quite unbelievably, Happy Donkey Hill. Place names are not protected in Wales and it is all too easy for names to disappear from memory in a generation. Acts of cultural vandalism such as this are increasingly common and there is currently very little one can do in the face of such insensitivity… except write songs!

On top of the stand in Faerdre Fach

There is a small basket of pretty flowers

And a new name for the place

The fair premises, formerly a hearth

Where the cowshed was ear the house

There is a bnb with a small pretty garden

And deadly silence about the palce

Emptiness where cattle called

Is it our names that are too much

Or the mouths of foreign people’s jaws?

Or is it understanding that is far

From the hunger for shelter in every heart?

And the land cries desperately

That we never forget

In the kitchen there is a screen

Showing a world in black and white

and the ffarm through a cctv lens

instead of the color of a child’s eyes

On the meadow below the fort

Where formerly there was the gold of August and its nourishment

There is a new owner proud his smile

Heeding not for longing

Is it our history that is so far away

Of the understanding of some so uneasy?

What a shock it will be the thing

To rid us of the stumbling block?

And the land cries desperately

That we never forget

Never forget