Song Lyric Translations

One aspect which sets Welsh folk music aside from other British indigenous music forms is that there is great emphasis on the written or spoken word. Melodies are often used as vehicle for supporting and heightening the literary prowess of the bard or author, rather than an end in themselves. Many songs also stem from, or follow very old poetic forms such as ‘tri thrawiad’ and contain complex internal rhyming and alliteration. As a result, melodies tend to be shorter and simpler when compared to their British and Irish cousins.

Whilst it was my original intention to print English translations of the song lyrics in the Dilyn Afon album booklet, it transpired that including these would have taken the booklet to over 70 pages which was beyond the capacity of a CD booklet (and my budget!). I’ve therefore made this page of translations for this who wish to know more about the songs and the stories behind them. I’ve also included the relevant background information next to each song.

Please note: These translations are mostly literal, rather than poetic attempts at translation. Translating Welsh verse into English and doing it justice is very tricky (and something which I’ve yet to master!)

Click on a song title to be taken to the song.

1. Cân O Glod I’r Clettwr

2. Dole Teifi / Lliw’r Heulwen

3. Y Ddau Farch / Y Bardd A’r Gwcw

4. Y Deryn Du

5. Taith Y Cardi

6. Y Fwyalchen Ddu Bigfelen

7. Lliw’r Ceiroes

8. Broga Bach

9. Cân Dyffryn Clettwr

10. Myn Mair

11. Ffarwel I Aberystwyth

Can O Glod I’r Clettwr (Song Of Praise To The Clettwr)

Were it not for T. Llew Jones’s original BBC Wales programme, this captivating song by Daff Jones would have disappeared forever – indeed it sat in the BBC archives for over 40 years before it saw the light of day again in 2016. It’s also peculiar also that it was not among the songs recorded by Roy Saer from Daff when he visited the old blacksmith in his home in Rhydowen in 1968. No record survives of the song’s origins or its title even, in oral or notated form, so we should therefore be grateful that it has survived at all.

The melody itself is fairly typical of many melancholic Welsh airs, but it also stands on its own as a succinct and unique composition. The words reveal perhaps slightly more about the songs origins, as the balladeer describes a life’s journey from birth to death along the banks of the Clettwr river which starts its journey on the marshland above Talgarreg village and flows into the Teifi near Dolbantau Mill on the border with Carmarthenshire. Though it’s evident in this case that the Clettwr river is the object of the author’s praise, the use of the word ‘hogyn’ (boy) is interesting. Since ‘hogyn’ is not a word generally in use in Southern Ceredigion, this suggests that the song originally travelled from somewhere more northerly (and from some other valley perhaps) and has been adapted for this river. I’ve therefore taken this a step further and ‘Ceredigionised’ the second verse in order to make it even more local.

Along the banks of the Clettwr, as a child I was raised,

And soothed to sleep by the sound of her waters

And there I played, a young sprightly child,

Trying to catch trout along the creeks of little Clettwr

The water turns mills as it goes on its way,

And the wheel of the factory too, like in the olden days

Among the thorns and the gorse, she emerges on the moor,

And the flow of wild flowers, around her precious banks

And when comes the day of my burial, break my grave,

Along the banks of the Clettwr, in the sounding of her waters

Dole Teifi / Lliw’r Heulwen (Teifi’s Meadows / The Colour of the Sunlight)

This track marries two songs along similar themes – love and deceit.

The first song, which forms the verses, has taken many lyrical and melodic forms in Ceredigion. It has also been noted down as Nos Galan and Y Bobl Dwyllodrus and appears in more than one manuscript and field recording. The melody in this version comes from the very north of the county and the words are an amalgamation of those sung by Thomas Rowlands, a farmer from Lledrod and Thomas Herbert, Cribyn (noted by J Ffos Davies around a century ago). Here an infatuated young man asks a friend for love advice and is told to play ‘hard to get’ – only to leave it too late and find out a year later that the object of his affection is engaged to another suitor (notably we never find out if it is his friend!)

The second part of the song which forms the chorus – Lliw’r Heulwen is from Mynydd Bach near Llanrhystud. It could easily be the same heartbroken young man as in the first song, as he pours out his affection, only to become exasperated by the apparent mercurial nature of a woman’s heart and resign himself to a life of singledom.

The green grass on the banks of the Teifi

Has tricked many a cow into drowning.

Many a girl has also tricked me

To leave the straight road for the desolate track.

One morning I was walking

Between the grass and the small trees.

There I met a neighbour,

One of the two-faced traitors.

The first thing I asked him —

How to love a girl and support her?

“Put aside her company for a year;

Little by little she will come to love you more.”

Colour of sunlight on the hills, colour of the lily upon the hill,

When you go from here, my dear remember this:

Your looks, your hand and your gracious manner, girl,

And your gentle, pretty nature has attracted my love.

I took that old fool’s advice;

For a year I gave her up.

After a year I went back

Thinking I would then have her company.

The girl gave an answer easy to understand —

“You have failed to get anyone else,

So, go far away, don’t come close,

I marry before the weekend.”

It’s very easy to recognise a hare, running in all haste;

It’s very easy to recognise partridges when they rise in a clamour;

The great oak amongst the little clover;

Woe is me that it’s not so easy to know a fair girl.

The mill must grind when it has water;

The smith must work while the iron remains hot;

The sheep must love the little lamb while it’s weak;

I must accept whoever is suitable for me.

Y Ddau Farch / Y Bardd A’r Gwcw (The Two Stallions / The Bard & The Cuckoo)

This is another track consisting of two songs which exhibit similar lyrical themes, this time anthropomorphism and animal communication.

The first, ‘Y Ddau Farch’ was collected from a native of Llangeitho in Ceredigion. The song is a conversation between two horses, with the older lamenting his lost youth and the redundancy of old age. It struck me that the merry nature of the original melody sat somewhat incongruously with the sad sentiment of the narrative and so this new version is intended to reflect this.

The second half of the track is an extract from the verses of ‘Y Bardd a’r Gwcw’ written by Daniel Jones or Daniel ‘Sgubor’ (1777-1859), a vagrant balladeer who sometimes took up residence in a barn in Castell Hywel. A conversation between a bard (possibly Dafydd himself) and the late returning cuckoo, this joyful exchange hailing the return of spring became very popular and travelled all around Wales, adopting a variety of melodies and words. Taken from the singing of Daff Jones, Rhydowen in 1968, recorded by Roy Saer.

When I was walking one morning,

Strolling from my little patch,

On the mountain I met

Two horses conversing.

The weakest horse

said to the stronger —

“Once, when I had respect,

I was as good a horse as you.”

“When I grew old and lame

I carried the corn to the mill,

And what I got

Were the poor leavings of husk.

“They took off my shoes

And sent me to the mountain,

And while I still breathe

I shall never go home.”

Oh Cuckoo, Oh Cuckoo, where have you been so long?

Before you came to the neighbourhood you quietened,

You missed your moment by two weeks almost,

You come at last with your merry song.

“I lifted my wing high up to the wind,

Thinking I would be here three weeks early.

Oh, don’t misunderstand, nor think so foolishly,

It was the cold north wind that held me back.”

Oh Cuckoo…(etc)

Y Deryn Du (The Blackbird)

This song of question and answer was once very popular across Wales. The form of conversing with birds has a literary tradition in Wales dating from the classical period of Dafydd ap Gwilym. Named canu llatai (llatai means love-messenger), such pieces usually involve a love-struck poet sending a bird with messages of love to a sweetheart. What sets this work apart from other llatai songs is that the author has not yet set his heart upon someone – instead the deryn du (a blackbird) acts as an avian dating service, listing all the apparently eligible local women!

Reviving this song required a little bit of detective work. The words were printed on a ballad sheet by Gomer Press, Llandysul, around the end of the 19th century but without a melody. I somehow managed to locate it in an obscure field recording of Tom Edwards, Flintshire in the British Library in London (recorded 1953). The accompanying notes said that it had been written around the middle of the 18th century by a mole catcher called David Jones from Llandysul and has also been noted as being sung by the famous balladeer ‘Dic Dywyll’ (Blind Dick) in Caernarfon in the 1830’s, so clearly this is a song which has travelled far and wide.

Blackbird, you who travels my lands,

Oh, you who know the old and new,

Will you give counsel to a young lad

Who has been pining for more than a year?

“Oh, come closer, lad, and listen,

To find out what ails you,

When either the world turns against you

Or you pine for someone’s love.”

Oh, it’s not the world that turns against me,

Nor do I pine for someone’s love,

But I see the fair girls becoming scarce

I don’t know where to turn for love.

“Do you like the old widow,

Her coat full and close to death,

Her black cows in her herd?

She will be of great benefit to you.”

I don’t like the old widow,

Her coat full and close to death,

Nor her black cows in her herd.

For a poor lad she isn’t suitable.

I don’t want her, Blackbird.

“Do you like the farmer’s daughter

who is a compassionate and merry flower,

who puts her money away in corners

And can leap a leap for every one of yours?”

Well, a hundred farewells to you, bird,

Well, this is the girl that I will go and ask.

While ship on sea and shingle in river

I will never want but for the farmer’s daughter.

Farewell to you, farwell to you, Blackbird.

Taith Y Cardi (The Cardi’s Trip)

Prior to Dr. Beeching’s infamous axing of local railway services in the 1960’s, Llandysul was one of many bustling regional stations on the West Wales line, transporting people, stock and goods across the country. A semi-Welsh version of the English ballad ‘The Charming Young Widow’, this tale of infatuation and deceit takes place on an ill-fated train journey from Llandysul to London.

Printed by Gomer Press around the turn of the last century, this is an adaptation of a macaronic song (a piece containing a mixture of two languages). It is unusual in the sense that it not only contains a lot of English, but that it does so in such a humorous manner. Llatai folk songs are known for often containing call and response in English and Welsh – indeed many Welsh ballads started life as English works – however the author of this ballad decided to use what could only be described as ‘Wenglish’ to tell his tale. It is unknown whether this was intended to be ironic, or is simply due to a poor grasp of the English language (the majority of Welsh speakers were monoglots at the turn of the 20th Century)

I live in Llandysul in Cardiganshire,

A letter informed me my uncle was dead.

And to go with great haste by train up to London

As hundreds of pounds was left me,’twas said.

So I was determined to go on my journey,

Book my ticket, first class, I was fine!

A widow and I side by side sat together

In the carriage was no one but us and no more.

Silence was broken by my purty companion

And then conversation, indeed ’til my brain

Was going on the dizzy—I almost went crazy

For the little fair widow that I seen in the train,

The little fair widow I seen in the train.

By this time the train it was come to the station,

A couple of miles from big big one in town.

The widow she say as she look thro’ the windows

Good goodness alive why there goes Mr. Brown.

Now she was disappeared, the guard whistle blowin’,

The train was a-moving but no widow appear.

With a puff and a puff it was off, I was afraid,

My watch! Oh! Where was it, and where was my train?

My purse and my ticket, loose tickets were gone,

When I found out my loss, indeed I was cryin’ —

“O dear, o dear, dear Mam what shall I do?”

The little fair widow, well she steals on the train.

The little fair widow, she steals on the train.

Y Fwyalchen Ddu Bigfelen (The Yellow Beaked Blackbird)

Copied from the singing of Mrs. J Emlyn Jones in Ceredigion and noted in the Welsh Folk Society journals, this melody is a variant of Cân y Lleisoniaid, which was at one point popular throughout South Wales. The manuscript notes that the compiler had replaced half of the words (which are incomplete) with those of his own, interlacing them with English (this stems from a practice in Glamorgan where Welsh colliers met English workmen for the first time). I have therefore used the Welsh words written by Llew Tegid.

This is another song which features a conversation with a blackbird – however it could be debated whether this song could be included in the llatai category at all since the ‘beloved’ in question is not a woman, but Wales itself. It is in essence a song of hiraeth by a boy who has crossed the border into England and is longing for his homeland, embodied in song by the mellifluous calls of the blackbird.

Oh, yellow beaked black bird,

Enchant the heart with your early song.

Sweet notes of a merry heart

Wakes the choir of little birds.

Come and listen to the complaint of a boy

Who is in heartache night and day:

A cruel longing pursues him,

Longing breaks his sad heart.

Leaving the elegant vales of Wales,

Leaving the enchantment of the land of song,

O so difficult is separating

A pure Welshman from fair Wales.

Your notes evoke the hearts longing

As you tarry in the Englishman’s land,

In memories of Coed-fron

Where once your voice was so dear.

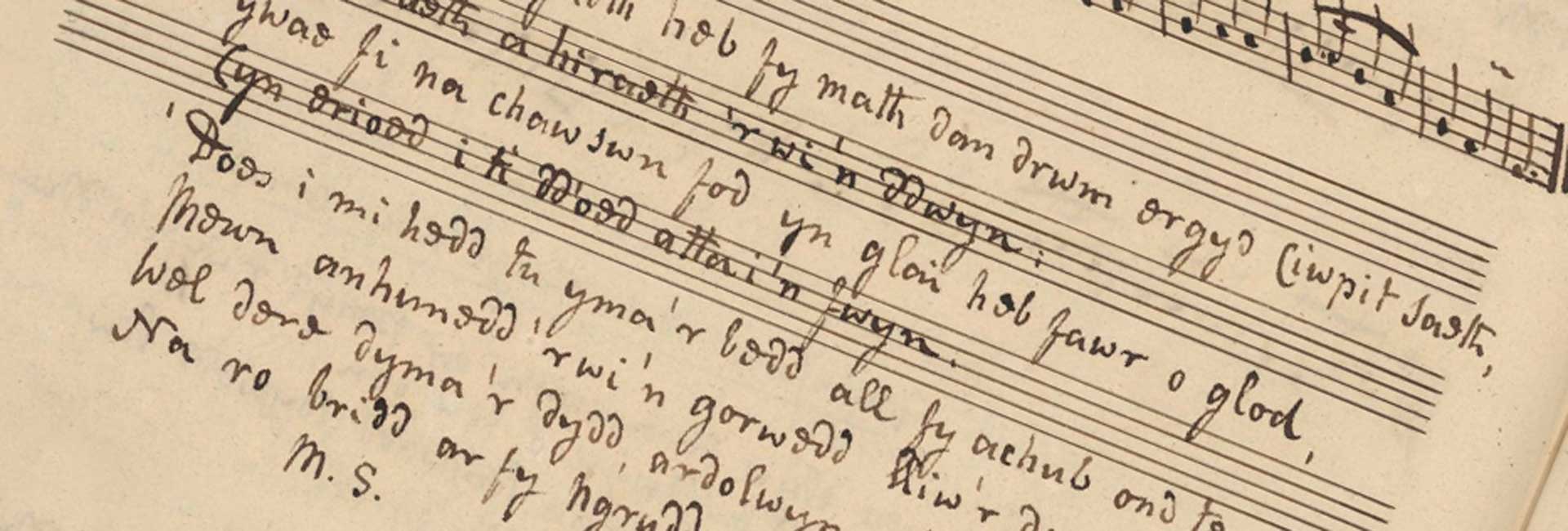

Lliw’r Ceiroes (Colour Of Cherries)

I came across this unusual melody in a large collection of manuscripts called ‘Melus Seiniau’ by the renowned song collector Ifor Ceri (also known as John Jenkins). Jenkins collected tunes and melodies from across Wales during the first half of the 19th century, including many from Ceredigion. Lliw’r Ceiroes (Colour of Cherries) is noted as originally being sung by Evan Thomas from Llanarth and it is recorded here for the first time.

The song follows the heartache of a young man who’s likely put his foot in it with his sweetheart and is now asking for penance. Lliw in Welsh can mean both ‘colour’ and ‘appearance’ and so Lliw’r Ceiroes or ‘Colour of Cherries’ in this case, is a nickname or term of endearment for his beloved who he is so desperately trying to win back. This song is a good example of Welsh verbal ingenuity; although not in strict cynghanedd (a metre unique to Welsh), it does contain a great deal of free alliteration.

Colour of cherries hear my complaint

And the penance that I bear.

Dear, beautiful woman, clear like the wave’s complexion,

For liking the good girl, the fair one, shining complexion,

Was to live, despite the wound beneath my breast.

I’m enslaved without my peer, below the blow of Cupid,

Doubt and longing I bear,

Woe is me that I could not be hidden away without much praise

Before you come dearly to me.

Give me peace, and save me from my state

I’m tired and sleepless complexion,

Come the day, please set me free,

Do not put earth on my cheeks, perfect woman.

Broga Bach (Little Frog)

Collected from the Llandysul area at the turn of the last century by a member of the Welsh Folk Song Society, this uniquely Welsh version of the Anglo-American tune ‘Frog Went a Courtin’ is almost unrecognisable from the popular tune which inspired it. This song was noted down in the mixolydian mode, a musical scale highly uncommon in Welsh folk music and therefore exudes a slightly eerie quality which is very different to the frivolous and merry nature of the English original.

There are lyrical similarities between the two versions, which could be said to be akin to a nursery rhyme – however the uncanny nature of this melody takes it in a different direction altogether. Only two verses were noted down in the Welsh manuscript and so the rest of the song has been translated from the original to complete the story.

Froggy went a-wooing ride, twy wy ei di o

Am i dym da e dym to,

When upon his high horse set

Am i dym da e dym to.

Little mouse did little froggy spie, twy wy ei di o

Am i dym da e dym to,

To make a wife and be his bride

Am i dym da e dym to,

Dearest love, do you see

I am very fond of thee,

And the kindly mouse to him

Answered with a beaming smile.

Take me to the gleaming church

We’ll be married in due course,

Mole he can officiate

Then lots of food to fill our plates.

Little frog, dear little frog etc

Cat came to the neighbourhood

Trapped the mouse near where she stood,

Little frog ran off for his life

Leaving there his dearest wife.

One duck on the millside pond

Swallowed little froggy – gone!

That was the ending of the two

And a romance which went askew.

Little frog, dear little frog etc

Cân Dyffryn Clettwr (Song of the Clettwr Valley)

This song, which is unique to the Clettwr valley, is noted in tonic sol-fa notation at the back of Hanes Llandysul (A History of Llandysul, 1896) by Gomer Press. I also uncovered a recording of Kate Davies, Prengwyn, singing it for Roy Saer during the sixties. Kate, a keen historian, author and singer, was likely the last person to have learned this song orally.

Originally composed by Edward Rees of Talgarreg, this song captures that most universal human desire for adventure and notes the sometimes capricious nature of the open road – or in this case, the sea. A tale of a mab afradlon (a prodigal son), the song’s protagonist leaves his cynefin alongside the banks of the Clettwr and goes to sea as a sailor, only to find that life is tough and that he soon has hiraeth (longing) for the comforts of home.

Yes, I spent a merry time

In the school in Llwynrhydowen,

And by following the fishermen

Along the banks of the Clettwr.

After finishing with the schools

I turned out to be a prodigal son,

And I went as a sailor boy

Beyond the sight of Clettwr Valley.

After the winds became silent

And the harsh waves became still,

The seaman felt disgraced —

He should return to Clettwr Valley.

I’ve walked the meadows of Aeron,

And embraced the blessed girls,

But the seaman much prefers

A fair girl from Clettwr Valley.

Myn Mair (By Mary)

This galargân (lament) was noted down from an elderly woman named Myra Evans in New Quay in 1963 by Robin Gwyndaf, who had been tasked by the Welsh Museum of Folk Life with recording as many old folk songs as possible before they passed from living memory. Along with his colleague Roy Saer, they amassed quite a remarkable collection of recordings. Myra was the last known bearer of this song.

This is the only surviving gwylnos song in Wales and was sung as part of a wake the night before a funeral by friends and relatives of the deceased. There is to this day a tradition in Wales of keeping bodies in the house and receiving visitors until the funeral and so this song would have formed part of a communal grieving process. The song is in essence a petition to Mother Mary that she (or anyone else with a VIP pass at the pearly gates) might watch over the soul of the recently deceased, which in the case of this song is likely to be a child.

The Catholic nature of the words indicate that this song is very old indeed. It seems it was sung and kept alive in secret for many hundreds of years following the reformation, with banishment from the chapel and public disgrace the likely outcome for anyone caught singing it.

My pennies I’ll give for the soul locked up,

My candle I’ll give in the parish church,

I’ll say mass fervently seven times seven times

To keep safe his eternal soul. Mary wills it,

Mary wills it, Mary wills it, Mary wills it.

Saint Paul and Saint Peter, all saints of heaven,

And Mary, Mother of God, entreat with all seriousness

That he may have peace, and rich relief,

Open paradise, and the arms of his Father.

Mary wills it, Mary wills it, Mary wills it.

Jesus’ Mother, most beautiful woman in the world,

Virgin Queen of all the heavens,

Pretty lily of the valley, fair rose of heaven,

Entreat with all seriousness on behalf of my friend’s soul.

Mary wills it, Mary wills it, Mary wills it.

Ffarwel I Aberystwyth (Farewell To Aberystwyth)

Ceredigion has a rich history of coastal trade and seafaring. This track conveys the hiraeth (longing) of the sailors as they left Cardigan Bay, naming the places and people they had left behind. The bulk of the track consists of a tune collected by Jennie Williams for the 1911 Eisteddfod folk song collecting competition. This melancholic air was sung to her by Dan Evans of Aberystwyth. Williams also collected songs from Evan Rowlands (a butcher on Pier St, famed both for his singing and the giant stuffed bear outside his shop) who had also heard the song being sung by local sailors.

The end section of the track is a fragment from a song Hwylio Adre (Sailing Home) in J. Glyn Davies’s book of Welsh sea songs and shanties. With the addition of this tune, the track forms a continual circle of departure and return, reflecting a common element of Ceredigion’s bygone coastal life. Many songs such as these would have travelled up and down the Welsh coast and across the sea, adding to the rich exchange in cultural, as well as material goods.

Farewell to Aberystwyth,

Farewell to the top of Maes Glas,

Farewell to the Castle tower,

And also Morfa Glas.

Farewell to Pen y Parce,

Farewell to Figure Four,

Farewell to the fairest girl

That ever opened a door.

Farewell to Llanrhystud

Where I’ve been many times

Loving according to my fancy,

But the work was in vain.

I did love her

For four and ten months,

We sometimes had bad weather,

Other times fair weather.

And sometimes I’d find her content

To listen to my complaint and cry,

But she gave her hand to another

And broke my heart.

To Calio I bid farewell,

To Calio I bid farewell,

Sailing home, sailing home . . .